Angband is a 1990 computer game in the subgenre of turn-based permadeath dungeon-crawling RPGs, also known as roguelikes. Very few people play Angband today, and most PC gamers have likely never heard of it - even when they've likely heard of NetHack and Dwarf Fortress. But did you know that the randomized equipment or "loot" so common in video games today was originally an innovation of Angband?

Today, these "loot lotteries" go far beyond just RPGs: the same blue "rares" and purple "epics" can be seen in the mainstream from mobile games to Fortnite, Destiny, and Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. We tend to talk a lot about the principles that make these systems compelling and even addictive. But what is less often discussed is how the concept's introduction into the mainstream of commercial games came largely through the vision of a single passionate Angband fan.

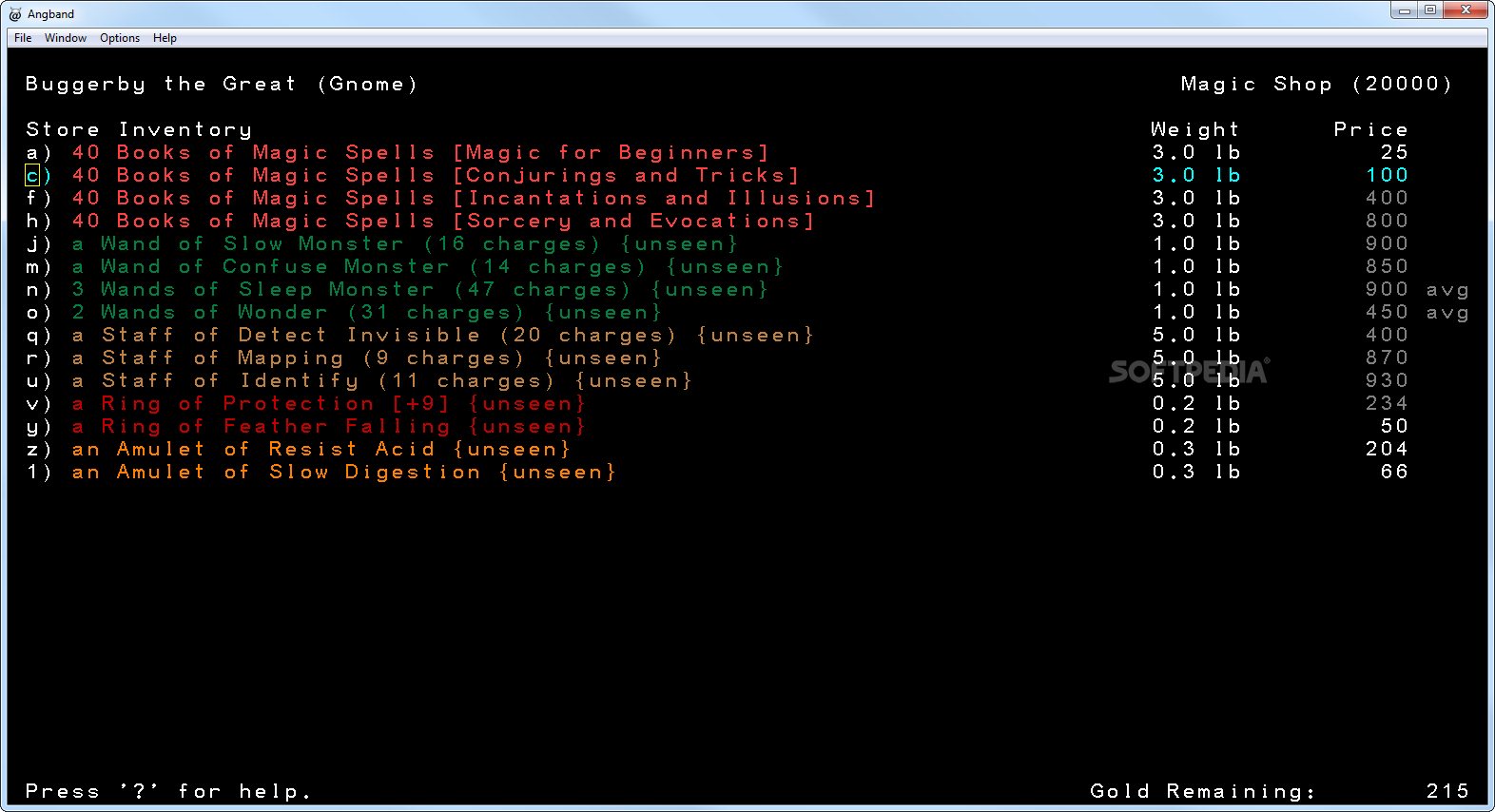

| |

| Angband's items aren't entirely colour-coded by their rarity, just by category... |

|

| ...However, artifacts are set apart by their names that glow in light blue. Might this choice be inspired by Bilbo's glowing sword, Sting? |

The roots of loot

Like its predecessor Moria (1983), Angband is an unoffical Tolkien fangame, pitting the player against Sauron and Morgoth. (It got away with this by being free and open-source; don't try doing this in a for-profit game.)

[EDIT 2024-07-09] This article originally failed to name the authors of Angband, a glaring omission for which I apologize. Angband was originally created by Alex Cutler and Andy Astrand. Their work was continued by Sean Marsh and Geoff Hill, who released the first public release of the game. More information can be found here: https://rephial.org/release/2.4.fk. I thank co-creator Andy Astrand for commenting below, which prompted me to realize the omission and very belatedly rectify it. [/EDIT]

|

| The Monsters & Treasure booklet. |

From the very beginning, the methods of generating loot were quite complex. In the original D&D game's second booklet, Monsters & Treasure, each monster is given a treasure type, for example: Giant, 5,000 GP + Type E. This indicates a giant lair will contain at least five thousand gold coins worth of treasure, plus potentially other things determined by a series of dice rolls on row E of the treasure types table. The table lists chances for several categories of treasure, each of which is rolled separately: separate chances for each type of coin, gems, and, finally, "Maps or Magic". For Type E, the entry for this last category reads:

30%: any 3 + 1 Scroll

(Gygax & Arneson. Vol 2. p. 22, Dungeons & Dragons. TSR, 1974.)

This means that the dungeon master rolls a d100, and on a result of 1-30, magic items are present. If so, the DM then proceeds to roll on the magic item lists: once on the Scrolls table to determine the type of the scroll, and three rolls for the other items of randomly determined categories (swords, potions, wands, etc.).

|

| Treasure Type E, used for giants, elves, and some of the more dangerous undead. |

So this all adds up to the dungeon master making up to 15 rolls generate the treasure in a giants' lair. That's the worst case scenario, of course - but, on top of those rolls, some items have further details to be determined: if the scroll is a spell scroll, then the spells written on it will need to be determined, and so on...

It's quite an involved process, and has not grown particularly more complex in later games - at least as long as a human brain and a pencil are used to do the generating. (Of course, a game master is not beholden to these guidelines, and may choose to instead place items using their own judgment.)

When computers began to be used for generating dungeons, they had no such limitations: a computer can make thousands of simulated die rolls a second. Now, the greater challenge lies in designing the rules in such a way as to generate results that are interesting, varied, and balanced, even after countless repetitions. On the other hand, the computer does not have the benefit of using common sense or imagination. It cannot choose to occasionally ignore a rule here and there, scrap a nonsensical result, or suddenly create an entirely novel type of item. The designer must specify all the rules and parameters exactly.

In the same D&D booklet, rules for magic swords were described. Swords were unique among magic weapons in that they could have personalities: the sword's alignment was rolled, as well as values for its intelligence and egoism. These were numeric statistics similar to those of player characters. If the sword's intelligence was sufficiently high, it was sentient and communicated telepathically, and potentially had a number of randomly chosen special powers such as detecting magic, flight, or telekinesis.

Sentient swords with a high egoism score were able to exert their influence on the wielder, initiating a battle of wills. Mechanically, this was a contested roll using the sword's egoism statistic against the wielder's statistics, with the winner gaining control over the other. These rules for mental conflict were designed to emulate the cursed swords in literature - specifically, Elric of Mélnibone's struggles with his runeblade Stormbringer in the many stories written by Michael Moorcock.

Randarts: Stormbringer goes electric

So, if loot has been randomly scattered throughout the dungeon in RPGs ever since RPGs existed, what made Angband so unique in its day? How did it impact the history of video games far beyond the roguelike genre, starting with Diablo (1997) and World of Warcraft (2004), like I claimed earlier?

The key innovation of Angband was randomly generated artifacts or "randarts". This feature is arguably what made Diablo such an addictive game - and a game that printed money for Blizzard Entertainment and has been a part of their winning formula ever since.

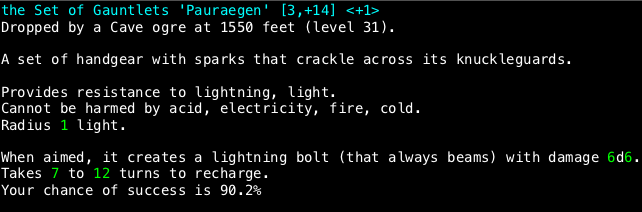

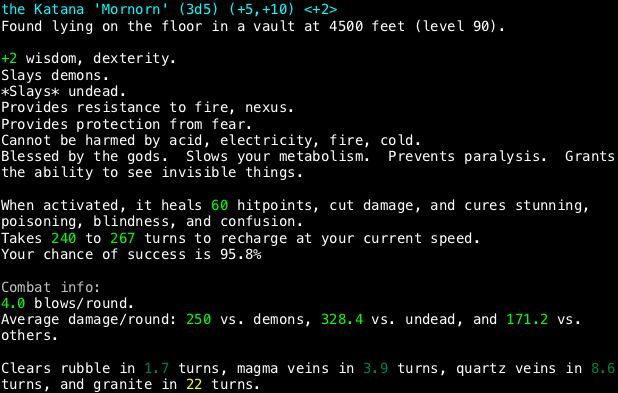

|

| Angband's randarts can get quite elaborate. |

|

| A weapon of Epic rarity in World of Warcraft. |

Randarts took a base item, such as a dagger or a tower shield, and modified it by adding multiple properties or "intrinsics", often with further randomized numeric values, some activated powers, and so on. By laying these randomized properties on top of each other in different combinations, an effectively endless variety of equipment is generated. For example:

the Mace 'Taratol' (3d4) (+12,+12)

Slays dragons (powerfully). Branded with lightning. Provides immunity to lightning. Cannot be harmed by acid, fire. When activated, it hastens you for d20+20 turns.

These randomly named artifacts were supplemented by fixed artifacts from the Tolkien legendarium, such as the Phial of Galadriel. Additionally, there were randomly-created magic items with no proper names but which appended a suffix "...of X" to the item's name:

Iron Helm of Seeing

Chain Mail of Resistance

Mithril Arrows of Frost

The "X of Y" naming is immediately recognizable to anyone who has played an MMORPG. Of course, many of these properties were directly copied from D&D as well. In the Angband fandom, and later roguelikes such as Dungeon Crawl: Stone Soup (2006), these properties are called "brands" (cf. "frost brand sword") for weapons, or more generally, "egos".

I was unable to find any direct source stating that the "ego" terminology in these games has its origins in the "egoism" statistic (in later editions, "Ego" score) of D&D's sentient weapons. But I think the lineage is pretty evident here, and this connection can probably be assumed.

Nevertheless, compared to pen-and-paper games, the huge amount of combinations that was possible through computer algorithms took the loot lottery to a whole new level, and is the secret sauce that made Diablo so popular and influential.

The devil in the design

(GI Show. Game Informer. YouTube. May 2019.)"Having realtime combat was an unusual thing." -David Brevik

The other unique feature of Diablo behind its popularity is its real-time gameplay. This was relatively rare in computer RPGs of the 90s, and the hack-and-slash games that did exist were often first-person affairs such as Might and Magic VI (1998) or The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall (1996). However, the real-time aspect of Diablo was not present during much of the game's development: in a design document from 1994, the game is described as operating "on a turn-based system", and a complex action-points system is alluded to. The same document reinforces the randomly created dungeons as "the heart" of the game. The roguelike origins of Diablo are immediately obvious.

While the creator of the game, David Brevik, was not afraid of taking some innovative departures from those roguelike roots (such as network-based multiplayer, a simple mouse-based interface, and a business model inspired by Magic the Gathering), there was one leap he was strongly opposed to taking: Diablo would never be a real-time game. In an interview with Ars Technica, he calls it his "his line in the sand" for what the game should be. It was turn-based or bust. It took a very long time for his colleagues and publishers (Blizzard, fresh off the success of the first Warcraft game) to get Brevik to agree to even test the idea.

"I said [to Blizzard], 'What are you guys talking about, no no no, this isn't one of your strategy games. We are really commited to making a turn-based game.' I love the sweat in a turn based game, especially in a roguelike, when you've made a turn, and you're down to one hit point, and you're frantically searching through your inventory ... I really loved that tension. And they said, 'Yeah, but, you know... real-time will be better.' ... There were two or three of us that held out 'til the bitter end."

(Diablo: A Classic Game Postmortem. GDC. YouTube. May 2016.)

When he finally implemented real-time gameplay into the Diablo prototype, Brevik immediately fell in love with it. Development continued on the now-realtime game with renewed excitement, and of course players would come to love the gameplay as well. Still, it is interesting to note that unlike many other roguelike trappings with which Brevik disposed of early on, the turn-based framework was one that he was not willing to let go of.

|

| Diablo. |

In an interview with Game Informer (YouTube, around 2h37m), Brevik is asked about the colour-coded loot which has been copied into so many other games. He directly credits Angband as the inspiration:

"What about loot rarity colours? Did you guys take that chart from anywhere, or was that invented in Diablo?"

"That came from a game called Angband. Back in college, I played a lot of roguelike games - including Rogue, which is where the term roguelike comes from. There were kind of different versions of this and there was Tolkien-themed ones ... they had a version called Moria, and somebody else made a version of it called uMoria, and then that changed into this game called Angband...

Anyway, so Angband was a game I played thousands, literally thousands of hours of. It was really the game that Diablo was based on. I wanted to take Angband, that original game, and make a modern version of it.

Because this was an ASCII game, you were the '@' symbol, and you were attacking the letter 'k' ... that was what the game looked like, it was just all letters. But there were different random items that you could get in the game and they had different colours. So if you found a rare one, the text wasn't just grey, it was blue text, and that meant that it was magic! So there were some colour variations to the text - yes, we had colour text back then, this new-fangled colour text stuff... So the idea came from that, and then we kind of expanded on it, but originally the idea came from Angband."

(GI Show. Game Informer. YouTube. May 2019.)

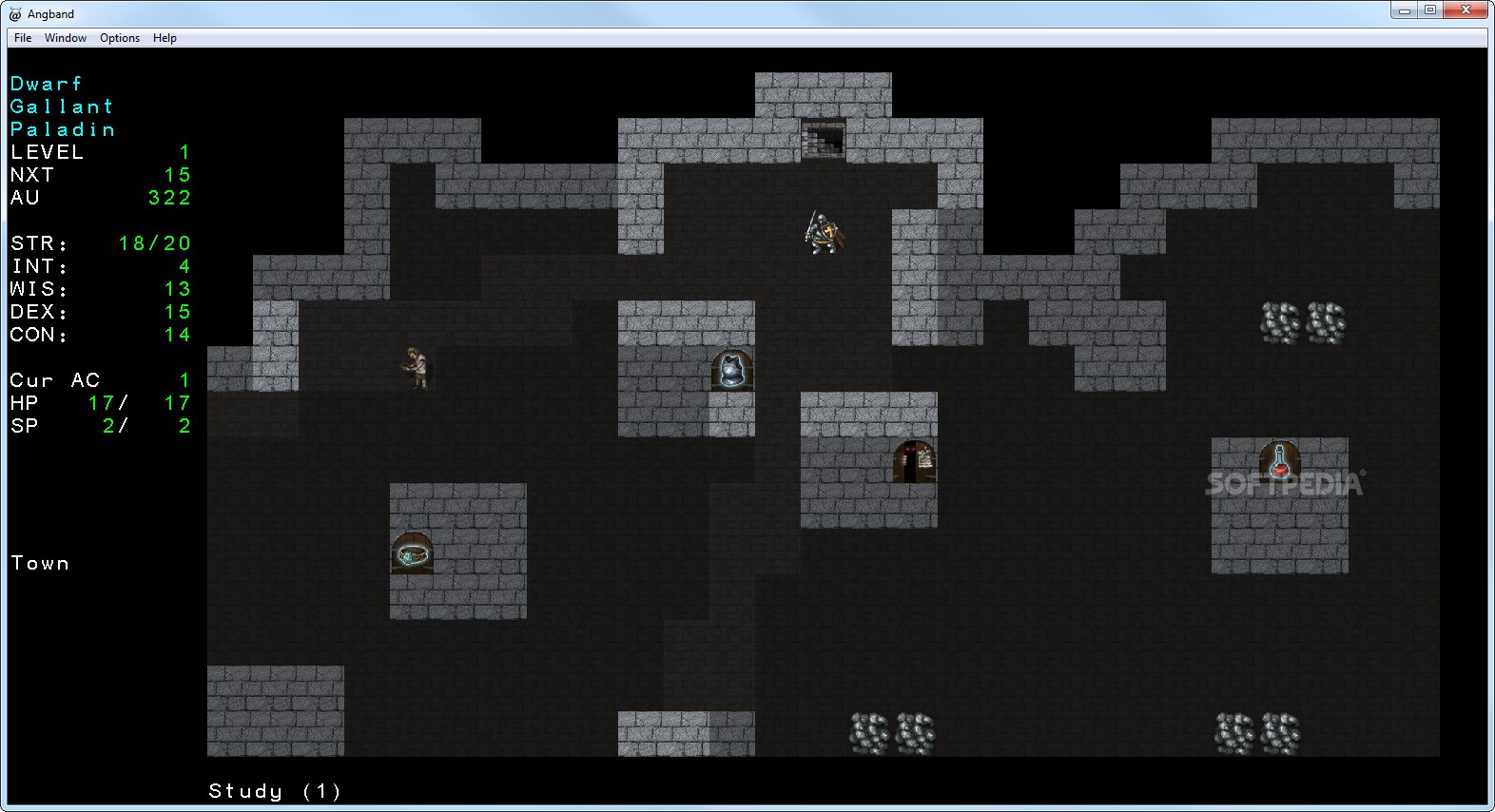

|

| These days, Angband is also available with graphics. |

Blizzard had a smash hit with Diablo and its sequel, and went on to make World of Warcraft, which was played by basically everyone. The influence of those games is visible in most games made today.

So, there you have it. Way back in the '90s, before the roguelites boom of the 2010s, roguelikes were silently changing the face of mainstream game design. And it was about much more than just randomly generated levels. This example shows that there are many valuable ideas and design patterns that originate in the roguelike genre. And, there may yet be many more that could be borrowed into other genres which the mainstream doesn't know about. In the niches beneath a craggy ASCII exterior, there might still be nuggets of gold, just waiting to be mined.

![[mantoman.png]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjRqyfU3ZbnK-XYXIj79v4S0eEO_EUUKrQkTcCcOPUS6UDwccsc7HHZeitC52nZ_zUR9O8XD0nC5zRxCdDJw1mduBd9UVUcY4b6ePE9jToAHIEVf-wxFAQ3_zhA3uqQr3uSW0Tx5ROXToQu/s400/mantoman.png)